The Art of Chocolate. From the Finest Cocoa to Exquisite Chocolate. part 7

Published by Max Felchlin AG, Schwyz, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary. (2008)

The Transformation From Bean to Chocolate

The fermented and dried cocoa beans are packed in sacks made of coarse jute and shipped across the ocean. They are then transported along the Rhine and unloaded at the port in Basel and put into storage. The chocolate manufacturers small warehouse in Schwyz only has the capacity to hold the quantity of beans that are used on a daily or weekly basis and that will be processed in the near future. Howover, before storing, Felchlin carries out one final, quasi inhouse grading of the delivered goods, separating them into two groups: those that are to be processed into Grand Cru chocolate and those that will become a blend of various origins.

Cleaning The daily quota is stored on pallets next to the cleaning machine. In industry, the cleaning process is fully automated, however, with a small producer of top-quality chocolate such as Felchlin, a single individual performs the first step in the cleaning process, which takes place in four stages, using three machines. This individual cuts open the sacks and casts a watchful eye over the contents as they are poured into the cleaning facility. This inspection is the last control before processing; after all, the cocoa beans could have become mouldy during the long sea passage in the ships hold. If the sacks were emptied automatically, this deterioration would go unnoticed with disastrous consequences for the final quality.

During cleaning, a magnet first removes any bits of metal. A blower then extracts dust and dirt, wood and fragmented beans. Finally, using a combination of gravity and vibration process, everything thats heavier than the cocoa beans is removed from the machine, for example, small stones. The cleaned beans are then transferred to a funnel-shaped silo and, from there, fed via an intermediate silo into the reactor below, where they are sterilised: pressurised, hot steam at a temperature of 150-170C kills all germs in just three to five seconds.

Roasting In the production of first-class chocolate, roasting the cocoa beans is equally as importants asfermentation. Roasting reduces the water content of the beans from about 6.5 percent to about 2 percent; the shells loosen, the colour darkens and the roasting aromas develop. Traditional drum roasters, such as are used at Felchlin, may appear outdated but thanks to their size, they are easy to monitor and handle; this enables rapid intervention in the roasting process. These traditional drum roasters are gas powered (of course, everyone is familiar with the immediate respones time of gas to simple manual adjustments from experience in a domestic kitchen). In order to achieve a uniform roasting, the beans are turned and mixed continuously in the drum and then discharged and fed into the cooler below. At this stage, a cocoa bean would not taste very different to a coffee bean to a certain exent, coffee and chocolate contain the same active ingredients; on account of its 50 percent cocoa butter conten, the cocoa bean is softer and without aroma.

More on Roasting:

Roasting pan: Open metal container that is heated over fire. This method is sometimes still used in the countries of origin when roasting cocoa beans for local consumption. (use: domestic)

Drum roaster: Large, rotating, gas-powered metal drum. The cocoa beans inside are moved and turned continuously for gentle, uniform roasting. This roasting in portions enables the roasting master to monitor the process and to quickly adjust the process to the different properties of cocoa beans depending on harvest and origin). (use; manufacturing)

Continuous roaster: Long, ventilated channels through which, from the left and right, hot air is blown. The channel is filled with cocoa beans or nibs, which slowly move from top to bottom and are thus heated continuously. The method is suitable for fully automated roasting of large, homogeneous quantities (mass production), but not if small quantities of different vareties have to be roasted. (use: industrial)

picture source: Vera Hofman.

Cracking The roasted, cooled beans are then fed through pipes into the winnower, where they are cracked and shelles removed: two rollers with blades attached rotating in opposite direction break down the beans. This is followed by separation: the shells are then removed by suction and the cracked beans, now called nibs, are sorted on a vibrating screen in stages, starting with the first fraction (very coarse), then the second to fourth fractions (increasingly fine), all of wich are further processed into high-quality chocolate; the fifth fraction (1-3 percent of the total cracked volume; very fine, almost dust-like, with remaining residu of shells and foreign matter) is discarded and can be processed into animal feed. The nibs are then directed into a silo using a jet of air.

Grinding The stone mill has round, rotating, horizontal stone plate, which grinds the nibs to a particle size of 100 microns, without any loss of aroma (in contrast to high-performance machines). The heat generated melts the cocoa butter. Tasting the warm, liquid cocoa mass would now reveal coffee and roasted flavours, as well as very fine, barely perceptible hints of fruit (minimum acid). In the ball mill, the mass becomes even more liquid. All small particles of cocoa have been ground and the cells have unlocked their flavours and aromas. The fruit notes are now stronger on the palate; there is an earthy aroma and a long finish. The desired complexity gradually starts to unfold in the cocoa mass. With industrial production, the next step is neutralisation, which involves water vapour releasing acids and bitter substances from the cocoa mass; for most Grand Cru qualities, this intermediate step is unnecessary. After fine grinding, the pure cocoa mass is ready.

Mixing Transformation of the cocoa mass into chocolate starts in the mixer: additives such as granulated or raw sugar, vanilla powder (not vanillin but ground vanilla pods), milk and/or cream powder and cocoa butter are blended with the freshly made cocoa pass. Sugar enhances the aromas; vanilla does not taste like vanilla but actually makes the chocolate smoother. Although as it often conceals any flaws in the flavour. If the cocoa mass is further processed into Grand Cru quality, in order to maintain the pure character of cocoa, vanilla is often omitted.

picture source: Vera Hofman.

Rolling The additives have transformed the cocoa mass into a chocolate mass, which is ground in the two-roll refiner to a particle size of about 120 micron; any sugar cristals still present in the mass after mixing are pulverised; the mouthfeel of the mass is dry and coarse. The five-roll refiner determines the fineness of the future couverture: for a Grand Cru, this should be between 12 and 15 micron. The human tongue cannot detect particles finer than 20 micron; any grittiness has disappeared. The chocolate mass is transferred to a trough, where the first roll picks it up and draws it into the rolling system, which now rolls the mass with an upward motion until it is wafer thin: on the uppermost roll, the chocolate mass has the appearance of a thin, brown, almost transparent film covering the metal. The cooled mass then flakes of and the flakes enter the conching process.

Conching This is the key process in refining chocolate; it was invented in 1879 by Rodolphe Lindt from Bern. Conching releases the very finest aromas in the mass and takes place in three stages: dry conching, plasticising and liquefying. Depending on the recipe and the machine, conching can take anything from a few to more than 70 hours. The temperature and frictional effect are generated by a type of agitator or mixer or by rolling in the longitudal conch. The most delicate couverture has to be monirated carefully; its often the worker at the machine who decides when a process is finished and when to intervene. Today, state-of-the-art, fully automatic conches are generally used. However, the best flavour is still achieved with longitudinal conches similar to those used in the nineteenth century. With dry conching, the flakes of chocolate mass are heated frictionally to between 60 and 90C. The dark brown, rather dry mass is turned and sirred. The rise in temperature causes the water to evaporate and this rising water vapour removes any volatile substances, such as acetic acid produced during fermentation. The mass has an initial water content of approx. 1.7 percent; this is reduced to just 0.6 to 0.7 percent.

During plasticising, the dry particles are covered in cocoa butter during constant stirring; the mass takes on a silky gloss. The senses now come into play with thr eyes making visual assessment of mixture. The aromas should unfold and merge; this is checked every three to six hours. The fine gloss starts to from. Once the desired gloss has been attained, liquid cocoa butter is added to liquefy the mixture. Before further processing, the warm couverture is then poured into heated tanks and stored for a maximum of two days.

The longitudinal conch In simple terms, conching transforms chocolate mass into a gorgeous product. The longitudinal conch is the most effective conching tool and, with its gentle action, it allows the most delicious flavours to develop. Felchlin still uses three longitudinal conches, each with four troughs and rollers, manufactured in the 1930s by U. Ammann in Langenthal. Thise conch looks rather like a paddle steamer and operates in much the same way: the wheel moves two horizontal connecting rods, one in front and one behind. The wheel rotates in the centre of the machine; the cast-iron troughs are located on either side. The lids used to cover the troughs are curved and painted a milk-chocolate brown. A steel roller is attached to the end of the connecting rod and this rolls the chocolate mass eveny backward and forward over a granite bed. The troughs are not heated; the intense heat that, depending on the duration of conching, is generated at the pedestal is the result of this motion, the constant friction and rolling action. Crashes and bangs can be heard as the mass smacks into the corners under the lid. However, the roller must never jump or knock. It is crucial that the right temperature is attained and this is no mean feat. There is no skill in simply pushing a button to start the heating process, however, there is an art to generating heat by applying just the right amount of friction. With longitudinal conches, it is possible to generate a temperature of 75C or more; 60-70C is the minimum. A certain temperature must be reached after 24 houres; if this does not happen, it cannot be corrected.

More on conching:

The conching machine is a special agitator for refining chocolate. Both physical and flavour-forming processes take place that are extremely important for glaze and aroma of the chocolate.

Slow conching: in the mechanical longitudinal conch, the chocolate mass is slowly rolled and aerated between granite stone and steel rollers for two to three says. The frictional heat has liquefying effect without any loss of the delicate aromas and fruit acids (see figures above).

Rapid conching: modern method that prepares liquid chocolate in just a few hours. Agitators with large shearing forces and rotational speeds can be used for rapid stirring, heating and the cooling of the mass.

Summer of 2011 visiting Fechlin and admire the longitudinal conching, thanks to Sepp and his wonderfull team.

Tempering The finished couverture to be moulded is cooled from 45-50C to 26-28C in a tempering unit and then re-heated to 29-32C. This produces uniform crystals in the couverture, which give the chocolate the desired texture and appearance.

Moulding, cooling and packaging The liquid, tempered chocolate is poured into the mould, cooled, knocked out of the mould and wrapped in compound foil or put into bags and then packed in cardboard boxes.

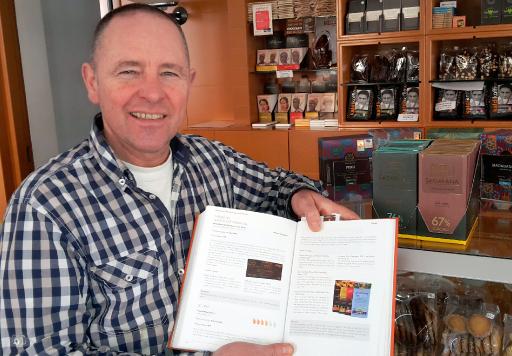

The presentation of the Grand Cru couvertures of Felchlin in my shop, sold in drops and bars with details to learn about and why this is such a fine chocolate!

next part: The Composition Every Detail Counts.

More on Felchlin and conching find out at chocolate friend Vera Hofman