Last episode: The Art of Chocolate From the Finest Cocoa to Exquisite Chocolate

By Vercruysse Geert, 2012-04-25

The Innovators In Pursuit of the New for 100 YearsFelchlin

Company histories are usually all about change, about leaps forward, highs and lows; they are a patchwork of differences. However, the Felchlin company history is different. In the 100 years since its foundation, it has been shaped by a remarkable amount of continuity:

- The products these have developed over time but always have satisfied a sweet tooth.

- The customers although they have changed, they have always stayed the same, pastry chefs and, more recently, also confectioners.

- The pursuit of the new the company founder, his son and todays management have always believed in innovation and have always been ahead of their time.

-The unorthodox mindset Felchlins management cared little for convention but looked for new approaches in order to arrive at different solutions.

In 1908, during the Belle Epoque period, 25-year-old Max Felchlin from Schwyz opened a shop. This timewhen women wore large hats and wide skirts and men sported carefully twirled moustaches and fine cloth. Felchlin sold honey and also made spread for bread that was aptly named Ambrosia. He spoke German and Swiss German and was also fluent in French and Italian. He was qualified merchant with boundless energy and had inherited his business acumen from his mother who, widowed at a young age, ran first a distillery and then a trading business.

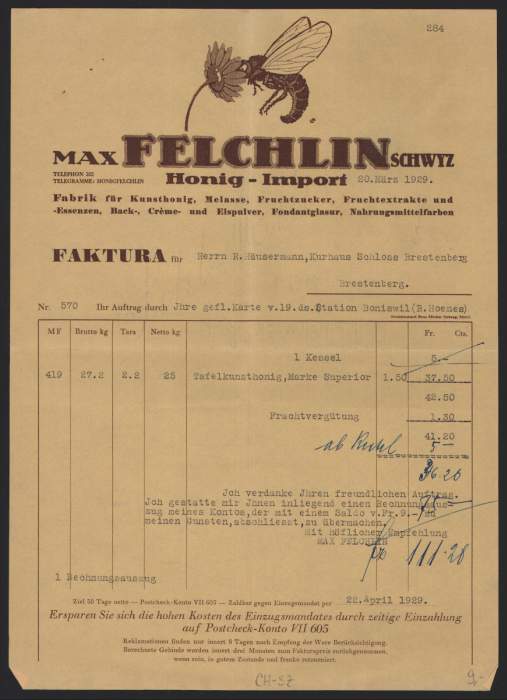

A time of change At that time, Schwyz was in a state of transition: the new postal building near the main square had just caused a stir, Zeppelin and other pioneers of aviation were launching airships that generated ripples both in skies and amongst the onlookers below. It is not surprising that the young, multi-talented Max Felchlin wanted to take his fate into his own hands. It was in his nature to try different things: he became chairman of the Mythen mountaineering club, was a passionate skier, sold typewriters, took lots of photographs and wanted to train as a photographer in Berlin. Hoever, his trip to the German capital was of short duration and, after returning to Schwyz, he founded the Kaufmnnischer Verein and became head of the Kaufmnnische Berufsshule. This chopping and changing from one thing to another all came to an end in 1913 when Felchlin set up the Honigzentrale Schwyz. He took on two permanent employees, thus demonstrating his decision to dedicate himself to this line of business. The young company went from strength to strength. Felhlin perfected Ambrosia, the spread made of honey, butter and fat known locally as Luussalbi. He became an adroit trader in honey; during the First World War when the honey trade had all but collapsed, Felchlin seized every favourable opportunity to import Italian, Dutch and American honey and went on to sell this not only in Switzerland but in other countries, too. As soon as the borders for both honey and people had reopened after the war, Felchlin embarked upon a fact-finding mission to America. In 1920, he visited honey suppliers, trading centres and a centre for the breeding of queen bees. He learnt all about the latest technologies. In 1922, back in Schwyz, Felchlin started to produce artificila honey. He also gradually expanded his product range. It became increasingly clear that his most important customers were bakers and pastry chefs, whom Felchlin supplied with semi-finished products. He sold baking powder, Vanilla-flavoured cream powder and even pure chocolate (Cacao Couverture Cacaobutter). This was quite remarkable. At the beginning of 1920s, Switzerland had hit rock bottom economically; it was shaken by strikes, foot and mouth disease was threatening agriculture, and it was at precisely this time that Felchlin decided to stake everything on chocolate, a luxury product. Once again, this demontrated his canny nose for business. Sure enough, the situation started to improve and Felchlin had made the right decision as Switzerland entered the Golden Twenties. As it was too complicated for pastry chefs and bakers to make chocolate themselves, Felchlins couverture was just the right product at just the right time. People danced the Charleston, wore short flapper dresses and sported Eton crops, watched with awe as high-performance racing cars sped through the mountains, discovered the cinema and the music halls and added a little sweetness to their new way of life. Felchlin was the first to offer chocolate couverture to pastry chefs. He also sold almonds, hazelnuts, sultanas, currants, coconut, figs, candied orange peel, egg white, malt extract, bakers ammonia, baking soda, sodium silicate, spices, pear-bread and gingerbread spices and fruit essences. As the name Honigzentrale did not properly reflect this impressive range of products, the company was renamed Max Felchlin, Schwyz, Spezialhaus fr den Konditoreibedarf.

Rechnung Schwyz 1929, Felchlin Honig-Import

Work in the laboratory History is not doubt that Max Felchlin was a resourceful businessman. However, he was more than just someone who was fortunate enough to have a few lucky breaks. In 1928, he set up his headquarters and home in Liebwylen. His laboratory was located directly below the office and this was where he experimented with new recipes until late in the night. The French novelist Victor Hugo once said, Genius is about patience. Felchlin liked to quote him and certainly lived up to spiret these words. He was dogged in developing both his products and company; his personal development was also remarkable. By the time he had reached middle age, Felchlin was an established businessman. He had a flourishing business, a beautiful home and office, a capable wife and three children. Thanks to his foresight, he had successfully achieved a clever mix of continuity and innovation. He confidently steered his company through stormy times, such as the world economic crises and the Second World War. At a propitious time, he purchased such vast quantities of sugar that the beams of the warehouse bowed under its weight. He developed the Pralinosa praline filling and the Sowiso cream powder. The extent of the popularity of Sowiso was largely due to fact that the next generation had a part in its succes: the youngest son of the family, Max Johannes, born in 1923, took the lead in selling Sowiso. He used his remendous wealt of ideas to marketthe cream powder that, with or without cookin, introduced fine vanilla, chocolate and caramel creams into domestic households. However, it was decades before Felchlin could hand business over the next generation. As is so often the case in companies managed by founder and owner, Max Felchlin senior initially despaired of his son. He finally handed over the reins to 39-year-old Max Felchlin junior in 1962 when he had proven himself by working at companies in Switzerland and the USA.

A marketing heavyweight First and foremost, Max Felchlin senior was a manufacturer who did his daily rounds of the factory and was actively involved in the production process. His son, on the other hand, was a marketing man who never spent any time in the production; he had products manufactured to meet the demands of the market. Despite this diffrence, they had one important thing in common: they were independent and wanted to remain so. Although the Schwyz region was Catholic through and trrough, Felchlin senior was a freemason; Felchlin junior was an untameable free spirit. He celebrated his independence by taking off on numerous study trips abroad. In January 1962, he took over the directorship of the company and, in the summer of that year, spent three months studying at the Harverd Graduate School of Business Administration in Boston. The company continued to flourish in Schwyz, mainly thanks to the established management team with Robert Lumpert (finance, sales), Felix Lappert (development, production) and Lilly Volpi (purchasing). Speaking of his extensive travels, Max Felchlin joked: My company never does better than when Im away. This was meant aa a compliment to his executive employees.

Perhaps Felchlin needed the freedom afforded him by his travels to Chili, India, Italy and the USA to continue to supply his tremendous wealt of ideas. On thing is certain: when abroad he always looked for new sales markets for his products. An extended trip to Japan opened up a new market there that soon became the most important export destination for Felchlin products. Whichever way you look at it, Max Felchlin was an unconventional company director. He once asked his employees about their hobbies. He urged those who did not have any to take one up. He believed it was important that his employees hadsomething else in life apart from work and that, should the need arise, they would be able to find solace in this is something bad were to happen to them. He also believed in emplyee training. In fact, so committed to this was he that his head of finance, Robert Lumpert, once asked teasingly, What is actually the purpose of our company: to train employees or to generate profits? Max Felchlin even wrote vocational training brochures entitled Werni Wild wird Beck-Konditor, thus demonstrating his talent for making less attractive areas seem more appealing to specific target groups. He was a talented marketing man. He had a quatation from Goethe mounted above the entrance to the company headquarters: The spirit out of which we act is the highest. However, Max Felchlin did not always displays this fine spirit himself: he could be very loud and overbearing. He burst into offices, forcing people who were talkng on the telephone to put down the receiver because he had something to say to them. If he didnt like someone, he made it quite obvious, once he had made up his mind, there was no changing it. On the other hand, he was both loyal and generous to those people he held in high esteem.

There is no doubt that Max Felchlin had a complex personality. He was an enigmatic figure: eccentric, with a touch of genius. His never-ending wealth of ideas was of tremendous benefit to the company. As competition increased and the domestic market became smaller, brilliant ideas were required and it was necessary to open new markets. In Swizerland, Felchlin tool pains to develop relationships with pastry chefs but was unsuccessful in this. However, he strengthened realtionships with wholesalers and the food service industry and cultivated commercial customers with sales promotions. He also developed the world-wide export side of the business; Felchlin headed the export department, after all, he was the most widely-travelled person in the company. He opened up the markets in America and Japan, accompanied by his American wife, Suzanne Felchlin-Eppes.

Felchlin acted with foresight and, in 1963, purchased a large area ol land in Ibach. In 1964, he openeda new warehouse on this land and, ten years later, it became the manufacturing site for all non-chocolate products. Nevertheless, however well-versed in the ways of the world, Max Felchlin kept his feet firmly on the ground and remained true to his roots. He commissioned a historian to research the history of the Felchlin family in the Middle Ages. He had a strong interest in local traditions, which he encouraged as well as he could. He supported the Chlefelen, a type of Swiss castanet, as well as the Geissechlepfe, the crack of the whip, by financing courses and offering prizes. Felchlin not only researched but also promoted, with a scientific meticulousness, Trentnen, the almost forgotten card game from Muotathal.

New training centre Since training was a subject so close to his heart, in the warehouse where the Sowiso cream powder was manufactured, Felchlin established Condirama, the industrys first training centre for pastry chefs and confectioners; this became an outstanding customerloyalty tool. At the opening in 1987, Max Felchlin again showed his unconventional side by dressing up as a radio reporter in order to find out what the public really thought of the new venture. Felchlin was just as singular when choosing a successor. In 1990, he founded the Verein zur Frderung der Wirtschaft und des Kulturschaffens (an association to promote the economy and cultural works), issuing the majority of votes to Max Felchlin AG and thus separating capital and decision-making authority. Since then, the company has experienced a very positive development. Max Felchlin appointed Christian Aschwanden as his successor; a food engineer and former Lindt manager, Aschwanden is a specialist in his field and, born in Schwyz, also completely conversant with local customs.

Condirama in Schwyz is a training centre for confectioners and pastry chefs.

We wish to earn money by providing services freely, honestly, cheerfully and optimistically, Max Felchlin remained true to this belief until his death in 1992. However, his successor had a long way to go before he could even start to think about making money again. The economy faltered, fey customers bailed out, small customers had to fight to survive and, in the midst of all this, the cantonal authorities for food control threatened to shut down chocolate production because it was housed in a simple wooden building in Seewen. The company was in the red.

New strategy In two closed meetings, the company management under Christian Aschwanden decided to tackle the problem head on. After all, previous company directors had demonstrated tremendous reserves of strength and the new management endeavoured to reinforce and develop the strengths of both production and sales. Management became a powerful team of specialists who knew how best to employ their strengths. By means of clever marketing, it was possible to win back customers and the new management also finally succeeded in securing a foothold with confectioners. Furthermore, production was made as flexible as possible, and this set Felchlin apart from larger suppliers. Finally, the most important step was the decision to concentrate production on high-quality goods. Felchlin wanted to control production quality from start to finish. This meant selection cocoa at source, transporting it over long distances and processing it with tremendous care. In 1999, in order to underline the high quality claim and standard, this fine flavour chocolate was named Grand Cru. One year later, the new factory was built on the plotof land bought by Max Felchlin in Ibach and this became the manufacturing site for all products. The success of new strategy was not long in coming. Customers were delighted and, in 2004, so was the strict jury: at the blindtasting of the famous Accademia Maestri Pasticceri Italiani, Maracaibo Clasificado 65% was crowned the best fine flavour chocolate in the world a great honour for the chocolatiers from Schwyz! This succes was all the sweeter in view of fact that Felchlin hadnt even entered the chocolate in the competition in the first place; the Italian importer had seen to that. Fechlin thus built on the succes of a previous award; at a blind tasting by bakers and pastry chefs in 1968, the outstanding qualities of dark couverture from Schwyz secured it first prize in the overall ranking !Whereas Max Felchlin seniors unconventional nature manifested itself in trying out new recipes, Max Felchlin junior was a man of unusual actions who liked to push through original ideas. Today, the unconventional is firmly anchored in the company strategy. Felchlin is not interested in compromise and believes in high quality in all stages of production, always translating its beliefs into actions. Customers appreciate this; they know where they are with Felchlin. As in the early days of the comapny, the majority of Swiss customers are still small traders and products are still predominantly semi-finished goods for confectionery and bakery products.

Today, 104 years since the foundations of the company, people no longer wear crinolines and sport twirled moustaches. Howevern they still love the exquisite confectionery that is produced using Max Felchlin AG products and today they also benefit from the added experience and expertise that has been developed over the last 100 years !

Hygiene und Idylle Felchlin in Schwyz

The Art of Chocolate. From the Finest Cocoa to Exquisite Chocolate. part 10

By Vercruysse Geert, 2012-03-31

Published by Max Felchlin AG, Schwyz, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary. (200 8)

A mellow sensation, marvellous aromas.

A luxury foodstuff with chocolates vast arry of aromas really ought to be suitable ingredients for use in complex dishes. However, in reality, its powerful flavour makes it a difficult spice that can only be used selectively, and certainly not in combination with just anything. Chocolate is a good complement to olives, olive oil, liver and roasted products and its outstanding in combination with fruits ans some herbs. For a long time, cocoa mass has been a vital ingredient in the Mexican dish,mole poblamo. The sauce that is served with chicken and turkey contains traditional crumbled cocoa mass, as well as onions, garlic, tomatoes, plantains, sesame, almonds, peanuts, raisins and prunes, coriander seeds, cinnamon, stale white bread, tortilla, chicken stock and a cocktail of four types of chilli and sugar.

The Spanish later adopted chocolate as an ingredient for sauces to complement game, for example, since the brown paste made the sauce go further. The Costa Brava is famous for its Catalan hare with almonds and chocolate (Ilebre amb xocolata). French cuisine also offers a dish of hare stewed in chocolate sauce (livre auchocolat) with a marinade of red wine, onions, garlic, carrots, leeks, thyme, bay leaves, nutmeg, pepper, lemon juice, ginger, cinnamon and cloves, which is thickened with dark chocolate, butter and chickens blood.

Lapin au chocolat.

Lapin au chocolat.

Italy has a dish comprising veal tongue in chocolate sauce (lingua in dolce forte), which is made of dark chocolate, sultanas, pine nuts and whit-wine vinegar, as well as hare in chocolate sauce (lepre dolce forte), which is less coplicated than the French version. In view of all the exquisite dishes featuring hare in chocolate, we could well ask ourselves whether the now traditional chocolate Easter bunny is perhaps the dessert version

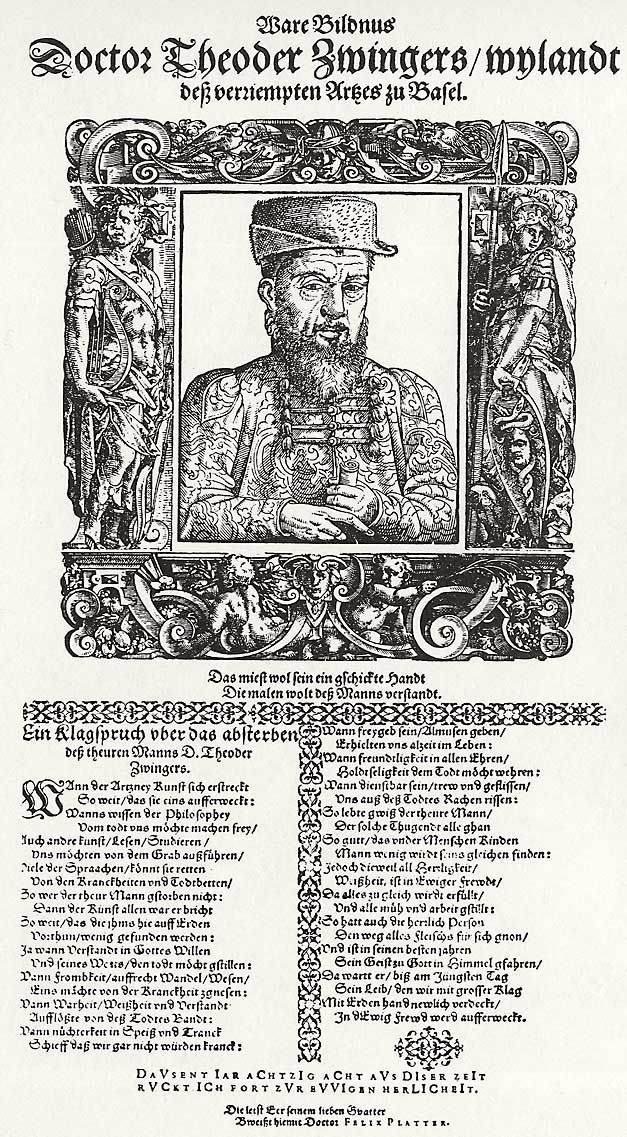

FOR HEALTH AND WELL-BEING In his book of herbs Theatrum botanicum published in 1696, Theodor Zwinger wrote that cocoa was both a food and a medication. Basel-born Zwinger (1658-1724) was regarded as one of the first real physicians and we can thus take seriously the healing properties he attributed to chocolate as used in the treatment of all kinds of illnesses and ailments. For example, to treat coughs and to strengthen the heart, to protect against stomach complaints, respiratory problems and phlegm, as well as diarrhoea and dysentery. When combined with nutmeg and almonds, he attributed aphrodisiac properties to chocolate, writing that it roused the libido and was given by wives as a love potion to their husbands.

The art of the confectioner So, when did solid chocolate appear on the scene? The chocolate bar? The chocolate that is not dissolved in a beverage or used in a sauce but that is enjoyed as a compact piece? The answer is at the beginning of the machine age when more and more work was rationalised and when processes that either difficult or impossible to carry out manually could be performed by machine.

Today, we have couvertures, the raw material of the chocolatier and the confectioner. We also have chocolate bars with just a few ingredients, such as sugar, vanilla and milk, as well as those with a greater range of ingredients, such as nuts (hazelnuts, walnuts, almonds, pistachios, macadamia), pieces of fruit, fruit aromas or fruit jellies (oranges, apricots, raspberries, grapes), or flavour combinations with coffee, nougat or caramel. Chocolate can take a lot of added ingredients. At the start of the new millennium, new combinations were launched on the market, mainly dark chocolate with lemon or grapefruit oil, fleur de sel, rosemary powder, cardamon and cinnamom, lavander and mint of curry spices from India, Thai curry, pink pepper or chilli.

Todays vast arry of confectionery and cakes would be inconceivable without chocolate. Originally, sweets did not contain any chocolate at all and were instead based primarly on oriental recipes perfected in the Viennese court. Pralines in the form of sugared covered in chocolate were first available in France in the 17th century. There are no known recipes for chocolate cakes dating back to before the 19th century. In 1832, a 16 year-old apprentice called Franz Sacher invented the now famous Sacher-torte. This features chocolate as a glaze and the method has since become indispensable for lots of exquisite sweets. The development of ice-cream-on-a-stick saw chocolate used as a solid covering that held the ice-cream together, for a while at least. The ptissier continues to make black-forest gateau and, of course,mousse au chocolate. The specialist are the chocolatiers and confectioners working only with chocolate. On nest pas dans la farine is their motto.

Danta Rosa de Jamaica & 75% Ujuxtes

Top chefs experiment In top restaurants, chefs experiment with chocolate and traditional recipes in order to create something new. The following dishes that were developed by a small selection of creative chefs sound simply divine:mousse au chocolate with olive oil (Martin Dalsass, Sorengo);terrine of goose liver in Riesling jelly with chocolate brioche (Hans-Peter Hussong, Uetikon);blood sausage with black chocolate, olives and hay-chocolatemousse(wuth aftermath, full cream and white chocolate; Stefan Wiesner, the Sorcerer of Escholzmatt);pamplemousse confits entiers avec gteau au chocolate noir coulant (Nicolas Le Bec, Lyon).

Franz Wiget from Adelboden restaurant in Steinen near Schwyz has devoted a lot time to the use of chocolate in the kitchen. This is partly at Felcjlins request since the company is keen to showcase the whole range of its aroma wheel of Grand Cru varieties in a top restaurant such as the Adelboden, which is situated near its manufacturing facilities. Its quickly became clear that working with chocolate and its characteristic range of flavours is a complex tast and that chocolate cannot simply be randomly combined with absolutely everything. The biggest obstacle is the sugar, explains Franz Wiget, which is why he works with finely-rolled Grand Cru cocoa mass that not contain sugar and, thanks to the skilled, restrained use of cocoa mass, has created some amazing and harmonious disches. The unsweetened, dark chocolate is particularly delicious in combination with olives, red meat and crustaceans. The folowing is a selection from the chocolate menu featuring the Arriba, Maracaibo and Cru Sauvage varities created by Franz Wiget for Felchlin:Croustillant with green-olivetapenade and chocolate( a tapenade is a spread over a thin triangular pastry base, a second piece of pastry is placed on top and the whole thing is baked until crispy; the tip of the triangle in then dipped in chocolate and croustillant is left to cool). Cappuccino with potato puree and chocolate(potato stock in a glass with cubes of chocolate, covered in foamed milk and with cocoa powder scattred over the top). Lobster soup withchocolate(made in the traditional way, thanks to the roast aromas that unfold during cooking, the lobster soup already tastes of chocolate; Franz Wiget simply adds two or three pieces of chocolate to the soup). Foie graswith chocolate and orange marmalade( the foie gras contains wafer-thin slices of Arriba cocoa mass that appear as black stripes when the foie gras is cut; the bitter-sweet marmalade goes with both the liver and the chocolate, the opulent aromas complement each other to perfection).

Beverage matching It only now remains to look at which can be enjoyed with chocolate.

n Marseille, it is the custom to break off a piece of pure, non-sweetened, hard cocoa mass and enjoy it with a little olive oil and an aperitif. Sweet wines in particular are a good complement to chocolate, for example, wines containing grape varieties such as Syrah, Rousanne or Grenache, wines such as Cte du Rhne, Banyuls, Chateauneuf-du-Pape, Bandol, as well as heavy Sicilian and other Southern Italian wines that often reveal chocolate on the palate during tastings.

n Marseille, it is the custom to break off a piece of pure, non-sweetened, hard cocoa mass and enjoy it with a little olive oil and an aperitif. Sweet wines in particular are a good complement to chocolate, for example, wines containing grape varieties such as Syrah, Rousanne or Grenache, wines such as Cte du Rhne, Banyuls, Chateauneuf-du-Pape, Bandol, as well as heavy Sicilian and other Southern Italian wines that often reveal chocolate on the palate during tastings.

The volatile aromas of distillates, such as Cognac, Armagnac or single-malt whisky, are simply superb in combination with the aroma and flavour of chocolate and can be enjoyed, for example, when unwinding at the end of a long day, to finish a delicious meal or simply on their own, since this is the union of two highly compatible partners, a marriage with fine prospects for a long, lasting finish. The reserve is also just as effective: chocolate containing spirits or liqueurs, for example, kirsch or absinth, cognac or whisky chocolate bars. Then, of course, there are alcohol-filled chocolates (ganache).

The volatile aromas of distillates, such as Cognac, Armagnac or single-malt whisky, are simply superb in combination with the aroma and flavour of chocolate and can be enjoyed, for example, when unwinding at the end of a long day, to finish a delicious meal or simply on their own, since this is the union of two highly compatible partners, a marriage with fine prospects for a long, lasting finish. The reserve is also just as effective: chocolate containing spirits or liqueurs, for example, kirsch or absinth, cognac or whisky chocolate bars. Then, of course, there are alcohol-filled chocolates (ganache).

Chocolate has the reputation for being an aphrodisiac and is a subject of heated discussion. However, if this is true, then the effect must be more in our minds than the result of any physical reaction since chocolate has not been scientifically proven to contain large quantities of any arousing substances.

Theres no doubt that, two to three hunderd years ago, the healing power of chocolate was much more pronounced than it is today. However, if we consider the number of chemicals the human body is subjected to today in the 21th century compared with the 17th century, how many substances modern man takes on a daily basis, such as vitamin pills and contraaceptive pill, then the little bit of magic present in chocolate is really not going to make that much of a difference, either to the invalid or to the lover.

However, we can console ourselves with the knowledge that chocolate is uplifting, that it is a quiet pleasure containing essence that help us to overcome lifes bitter disappointments, reinforcing what the infant realises the first time it suckles at its mothers breast, namely sugar means love and a feeling of security. This first formative experience of taste is the most important and remains with us throughout our lives, even if, in adulthood, we have to learn self-denial and prefer to eat something savoury rather than chocolate. Self-denial has been the enemy of chocolate for years, ever since the ideal beauty has been that of the ultra-slim model, dictating fashions and setting the tone of society in which we live.

Wherever self-denial is involved, quality of life inevitably suffers. However, a specific pleasure is a way out of dilemma we experience when caught between the opposing states of joy, frustation and desire for good healt: we dont want just anything; we want the best. For example, chocolate that has been manufactured with the utmost care and devotion to detail, every step of the way as at Felchlin. In short, we want a superior chocolate. Our own small piece of luxury.

next final episode:

The Innovators In Pursuit of the New for 100 Years (the history of Felchlin)

The Art of Chocolate. From the Finest Cocoa to Exquisite Chocolate. part 9a

By Vercruysse Geert, 2012-03-18

Published by Max Felchlin AG, Schwyz, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary. (2008)

The Pleasure

From Chocolate to an Agent of Delight

Solid chocolate that does not contain additives is perishable; it should not be left for too long before it is consumed as it will not improve over time. It should always be stored under dry conditions and at a constant temperature of between 12C and 20C; cold, heat and light are equally harmful. Under these conditions, it should keep for a relatively long amount of time: dark chocolate for up to two years, milk and white chocolate for up to one year. Dark chocolate has a longer shelf life than white chocolate, since the latter contains milk components wheraes dark chocolate contains oxidation-inhibiting substances, such as polyphenoles, for stability. Some additives reduce both suitability for storage and shelf life. These additives include milk and cream powder or nuts, which become rancid over time.

If stored in the fride, chocolate should be kept in a sealed, airtight plastic container to protect it from moisture and unwanted odours (such as cheese, pesto, cooked food), wich it would otherwise absorb. Before it is eaten, it should be brought to room temperature, as low tempearture prevent the aroma from unfolding fully. If chocolate is subjected to a large change in temperature from a very cold to a very warm environment, moisture can release the sugar from the chocolate and, when the water has evaporated, the sugar remains on the surface in the form of crystals; this is known as sugar bloom.

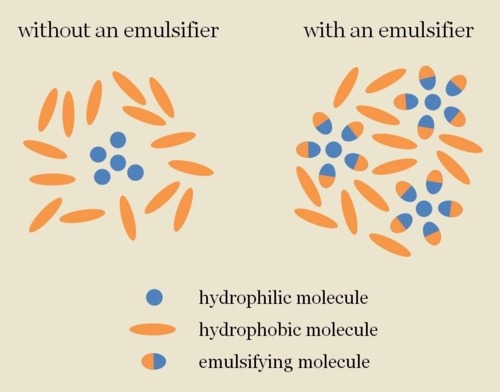

A typical chocolate bar is a mixture of cocoa butter, cocoa solids, sugar, and an emulsifier such as lecithin. The cocoa butter and cocoa solids are made up of hydrophobicmolecules (from the Greek for water fearing) while sugar is generally hydrophilic(also Greek, meaning water loving). Hydrophilic and hydrophobic molecules dont mix well, so an emulsifieris used to help blend the different molecules and keep them from separating over time.

If chocolate is stored at too high temperature, if it is exposed to the sun or subjected to the suns rays hotter than 32 to 33C, fat crystals froms and are deposited on the surface in the form of a white layer: this is known as fat bloom and is often mistaken for mould.

Similarly, fat bloom occurs when hydrophobic cocoa butter molecules separate from the rest of the chocolate and make their way to the chocolates surface. The specific causes of fat bloom are a bit more complicated and have been the focus of several scientificstudies. Who knew so much research went into something as simple as a chocolate bar?

Another danger is oxidation, which occurs if the chocolate is exposed too often to light and air. The fats react with oxygen and become rancid; the aromas vaporise. The higher the cocoa content, the better the chocolate is protected against oxidation. Chocolate is best stored in an airtight container in a dark place.

This basic idea of mixing hydrophilic and hydrophobic molecules also explains the driving forces behind chocolate bloom. Sugar bloom occurs when chocolate comes in contact with water. Because sugar mixes with water more readily than the fats in chocolate, any moisture that comes in contact with chocolate dissolves the sugar at the chocolates surface. As the water evaporates, a grainy white mess of sugar crystals is left behind.

An unforgettable drink Although the Spanish were the first Europeans to taste chocolate, by that time, the Mayas and Aztecs has been enjoying the cocoa for a very long time. In liquid form, hot or cold, chocolate has probably been consumed for a good 3.000 years. However, solid chocolate, as we know it today, has been eaten for less than 150 years. The native Mexicans ground the beans into a paste, added spices and pressed it into cakes. To make it into a drink, they scraped the required amound from the hard cake, poured it into a vessel and added water. This chocolate is nothing like the chocolate we drink today. The native Mexican nobility refined the chocolate by adding ingredients such a vanilla, wild honey, agave juice and chilli powder. The conquistadors then adopted the basic recipe, including the vanilla, a New World plant but, because the flavour of the xocolatl of pre-colonial Mexico was too bitter, transformed it to their taste by adding lots of sugar, aniseed, cinnamon, almonds and hazelnuts. The resulting drink was praised for its energising and restorative effects.

A table lined with all the standard tools for preparing chocolate: a ceramic comal or griddle for roasting the beans, a metate or volcanic grinding table, a molcajete or mortar (upper right) for mixing the cocoa with other ingredients and a molinillo (lower left) used to produce the delicious foam that tops Mexican hot chocolate

For many years, chocolate was expensive and exclusive and was enjoyed only by the European nobility. The Spanish monopoly only crumbled when competition emerged from countries such as Portugal and England, and this brought prices tumbling down. Although the raw product became cheaper, chocolate was still not consumed by common man, such as farmers and craftsmen, but it remained the exclusive preserve of the upper middle classes. Chocolate houses opened serving the most expensive of tree new drinks, namely chocolate, coffee and tea. People enjoyed these beverages in vast quantities whilst discussing the topical issues os the day.

The chocolate consumed today consists mainly of cocoa powder and sugar or instant powder; this can be stired into a hot or, in case of instant products, also into a cold liquid. Although, today, real hor chocolate is very much rarity, chocolatiers and specialist shops and outlets that value authentic, honest and first-class products are increasingly re-introducing it. After all, its basically quite simple to make: take a few peices of chocolate (preferably different varieties of Grand Cru with varying cocoa contents up to 100 percent), dissolve them in hot, fullfat milk, stirring continuously, and there you have it: a delicious, slightly foamed hot chocolate drink.

Hot Chocolate, Raimundo de Madrazo y Garreta (Spain 1841-1920)

Next time: A mellow sensation, marvellous aromas.

The Art of Chocolate. From the Finest Cocoa to Exquisite Chocolate. part 8

By Vercruysse Geert, 2012-03-02

Published by Max Felchlin AG, Schwyz, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary. (2008)

The Composition

Every Detail Counts

The couverture is now ready. The confectioner uses it as raw material for individual chocolates, for solid chocolate and for other in-house specialities. The couverture contains more cocoa butter than chocolateand this enhances its flow flow properties to facilitate pouring or when used as a coating in further processing. Whether in the form of button-sized discs or heavyweight bars, this soberly-wrapped raw product easily contains 600 different natural aromas: individual components that cannot be fully perceived, imagined or identified either on the nose or the palate. This analysis and counting of the individual substances is performed in the laboratory using a gas chromatograph: depending on their mass and structure, individual molecules pass through a tube at different speeds and can thus be identified and counted on the basis of their separation.

However, pleasure is not a mathematical equation and the senses are not a computer program. Like wine tasting, they rely on other factors, such as the character and physical and emotional well-being of the taster, on the weather, the temperature and time of day. The senses are concerned with chocolate as a whole but each sense approaches it from a different angle.

First of all, we look at chocolat with our eyes. Whether a bar of solid chocolate or an individual chocolate, an Easter bunny or mousse-its very colour attracts our attention. And this attention has to be deeply rooted in our souls. There is a tendency to associate very dark foods, such as coffee, chocolate, truffles, caviar and porcini mushrooms, as well as plum cake, with arousal and luxury, wrote Magaret Visser, Canadian professor, in her book The Rituals of Dinner. In our innermost beings, we believe that this special dark matter has be meaningful and originated from ancient times.

A bar of Grand Cru chocolate has a silky-matt gloss, whereas straightforward industrial chocolate looks like a plastic sample. The next two senses determine further differences: when a piec of chocolate that has been rolled backward and worward by a longitudinal conch for hours is broken of, it makes a soft snap, a tone in a minor key, almost like a soft sigh. The snap of chocolate that has been manufactured rationally and less elaborately is higher and sharper. The reason for this different music is the cocoa varity and the quality of the beans.

Our sense of touch tells us more. Rubing a few fragments of chocolate between our index finger and thum warms the chocolate, thus releasing the volatile aromas. Biting into the chocolate tells us about its consistency, whether it has hard or soft structure; again, the sound it makes as we bite into it is important, but the feel of it on the tongue (called mouthfeel) is also crucial.

We now allow the chocolate to melt on the tongue. One of the secrets of pleasure of chocolate is its mellow sensation: chocolate melts at 33C, which is just 3C lower than thetemperature of teh human body, the temperature that is the closest to the soul. The cocoa butter starts to melt away and the fat is broken down, the aromas unfold and develop and, because the melting point of chocolate is just a few degrees below that of body temperature (which is why chocolate initially feels cool on the tongue), chocolate can also have an intimate, comforting effect. Whilst the chocolate melts on the tongue, the taste papillae pick up all of many flavours and trigger a signal to the brain, where the taste memory is challenged. How can these flavours be graded, where classified? Chocolate we know, but what about everything else? This all has to be registered individually.

The tongue first detects the basic tastes: sweet, sour, bitter and also salty, or least mineral. By holding our breath for a momentthen breathing out gradually through the nose, we can detect the volatile aromas and basic flavours, as well as further nuances: spicy, strong and distinct (vanilla, cinnamon, cloves and other opulent, Christmassy components), refreshing and fruity (cassis, apricot and wild berries), floral (orange blossom and rose), vegetal ( brushwood and truffles), nutty (almond and macadamia), as well as roast aromas (coffee, tea or caramel) and other independent aromas (tobacco, butter, honey or beeswax). All these flavours, substances, essences and a few more nuances that can be identified with the human sensory organs and a little practice are also found in wines. Listing flavour nuances from the world of botany and other areas of life may be problematic when trying to understand complex flavor landscapes; it is often difficult to put impressions into words. However, a landscape consists of details and identifying these details, one after the other, underpins its incredible richness whether chocolate, wine or a truffle that has just been unearthed and cut open.

THE COMPOSITION OF THE COCOA BEAN

The cocoa bean contains more than 50 percent cocoa butter. Protein and starch account for a good 10 percent of the weight of the bean, with many other substances making up the balance, including the essences, which act as a stimulant and which also give us foodfor thought. On the one hand, the variety of the aromas stimulates the senses and, on the other hand, these substances also have a beneficial effect on our physical and emotional well-being. The cocoa bean contains caffeine, theobromine, serotonin and phenethylamine all substances that act as anti-depressants, anti-stress agents and that are thus relaxing. Theobromine and caffeine are alkaloids that stimulate the central nervous system and also act as diureticts.

Content of the cocoa bean: Caffeine 0.2%, sugar 1.0%, Theobromine 1.2%, minerals, salts 2.6%, water 5.0%, Polyphenoles 6.0%, Cellulose 9.0%, organic acids 9.5%, Protein 11.5%, cocoa butter 54.0%

BASIC CHOCOLATE RECIPIES

The flavour of the cocoa is determined by its origin, bean variety and processing. Chocolate is made from either single-variety or from blends of different beans. Sugar is also added. Mixing in milk powder produces milk chocolate. White chocolate does not contain any cocoa solids, only cocoa butter.

DARK CHOCOLATE: 70 % cacao and 30% sugar

MILK CHOCOLATE: 35% cacao, 40% sugar and 25% milk powder

WHITE CHOCOLATE: 35% cacao butter, 40% sugar and 25% milk powder

next time The Pleasure From Chocolate to an Agent of Delight

The Art of Chocolate. From the Finest Cocoa to Exquisite Chocolate. part 7

By Vercruysse Geert, 2012-01-25

Published by Max Felchlin AG, Schwyz, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary. (2008)

The Transformation From Bean to Chocolate

The fermented and dried cocoa beans are packed in sacks made of coarse jute and shipped across the ocean. They are then transported along the Rhine and unloaded at the port in Basel and put into storage. The chocolate manufacturers small warehouse in Schwyz only has the capacity to hold the quantity of beans that are used on a daily or weekly basis and that will be processed in the near future. Howover, before storing, Felchlin carries out one final, quasi inhouse grading of the delivered goods, separating them into two groups: those that are to be processed into Grand Cru chocolate and those that will become a blend of various origins.

Cleaning The daily quota is stored on pallets next to the cleaning machine. In industry, the cleaning process is fully automated, however, with a small producer of top-quality chocolate such as Felchlin, a single individual performs the first step in the cleaning process, which takes place in four stages, using three machines. This individual cuts open the sacks and casts a watchful eye over the contents as they are poured into the cleaning facility. This inspection is the last control before processing; after all, the cocoa beans could have become mouldy during the long sea passage in the ships hold. If the sacks were emptied automatically, this deterioration would go unnoticed with disastrous consequences for the final quality.

During cleaning, a magnet first removes any bits of metal. A blower then extracts dust and dirt, wood and fragmented beans. Finally, using a combination of gravity and vibration process, everything thats heavier than the cocoa beans is removed from the machine, for example, small stones. The cleaned beans are then transferred to a funnel-shaped silo and, from there, fed via an intermediate silo into the reactor below, where they are sterilised: pressurised, hot steam at a temperature of 150-170C kills all germs in just three to five seconds.

Roasting In the production of first-class chocolate, roasting the cocoa beans is equally as importants asfermentation. Roasting reduces the water content of the beans from about 6.5 percent to about 2 percent; the shells loosen, the colour darkens and the roasting aromas develop. Traditional drum roasters, such as are used at Felchlin, may appear outdated but thanks to their size, they are easy to monitor and handle; this enables rapid intervention in the roasting process. These traditional drum roasters are gas powered (of course, everyone is familiar with the immediate respones time of gas to simple manual adjustments from experience in a domestic kitchen). In order to achieve a uniform roasting, the beans are turned and mixed continuously in the drum and then discharged and fed into the cooler below. At this stage, a cocoa bean would not taste very different to a coffee bean to a certain exent, coffee and chocolate contain the same active ingredients; on account of its 50 percent cocoa butter conten, the cocoa bean is softer and without aroma.

More on Roasting:

Roasting pan: Open metal container that is heated over fire. This method is sometimes still used in the countries of origin when roasting cocoa beans for local consumption. (use: domestic)

Drum roaster: Large, rotating, gas-powered metal drum. The cocoa beans inside are moved and turned continuously for gentle, uniform roasting. This roasting in portions enables the roasting master to monitor the process and to quickly adjust the process to the different properties of cocoa beans depending on harvest and origin). (use; manufacturing)

Continuous roaster: Long, ventilated channels through which, from the left and right, hot air is blown. The channel is filled with cocoa beans or nibs, which slowly move from top to bottom and are thus heated continuously. The method is suitable for fully automated roasting of large, homogeneous quantities (mass production), but not if small quantities of different vareties have to be roasted. (use: industrial)

picture source: Vera Hofman.

Cracking The roasted, cooled beans are then fed through pipes into the winnower, where they are cracked and shelles removed: two rollers with blades attached rotating in opposite direction break down the beans. This is followed by separation: the shells are then removed by suction and the cracked beans, now called nibs, are sorted on a vibrating screen in stages, starting with the first fraction (very coarse), then the second to fourth fractions (increasingly fine), all of wich are further processed into high-quality chocolate; the fifth fraction (1-3 percent of the total cracked volume; very fine, almost dust-like, with remaining residu of shells and foreign matter) is discarded and can be processed into animal feed. The nibs are then directed into a silo using a jet of air.

Grinding The stone mill has round, rotating, horizontal stone plate, which grinds the nibs to a particle size of 100 microns, without any loss of aroma (in contrast to high-performance machines). The heat generated melts the cocoa butter. Tasting the warm, liquid cocoa mass would now reveal coffee and roasted flavours, as well as very fine, barely perceptible hints of fruit (minimum acid). In the ball mill, the mass becomes even more liquid. All small particles of cocoa have been ground and the cells have unlocked their flavours and aromas. The fruit notes are now stronger on the palate; there is an earthy aroma and a long finish. The desired complexity gradually starts to unfold in the cocoa mass. With industrial production, the next step is neutralisation, which involves water vapour releasing acids and bitter substances from the cocoa mass; for most Grand Cru qualities, this intermediate step is unnecessary. After fine grinding, the pure cocoa mass is ready.

Mixing Transformation of the cocoa mass into chocolate starts in the mixer: additives such as granulated or raw sugar, vanilla powder (not vanillin but ground vanilla pods), milk and/or cream powder and cocoa butter are blended with the freshly made cocoa pass. Sugar enhances the aromas; vanilla does not taste like vanilla but actually makes the chocolate smoother. Although as it often conceals any flaws in the flavour. If the cocoa mass is further processed into Grand Cru quality, in order to maintain the pure character of cocoa, vanilla is often omitted.

picture source: Vera Hofman.

Rolling The additives have transformed the cocoa mass into a chocolate mass, which is ground in the two-roll refiner to a particle size of about 120 micron; any sugar cristals still present in the mass after mixing are pulverised; the mouthfeel of the mass is dry and coarse. The five-roll refiner determines the fineness of the future couverture: for a Grand Cru, this should be between 12 and 15 micron. The human tongue cannot detect particles finer than 20 micron; any grittiness has disappeared. The chocolate mass is transferred to a trough, where the first roll picks it up and draws it into the rolling system, which now rolls the mass with an upward motion until it is wafer thin: on the uppermost roll, the chocolate mass has the appearance of a thin, brown, almost transparent film covering the metal. The cooled mass then flakes of and the flakes enter the conching process.

Conching This is the key process in refining chocolate; it was invented in 1879 by Rodolphe Lindt from Bern. Conching releases the very finest aromas in the mass and takes place in three stages: dry conching, plasticising and liquefying. Depending on the recipe and the machine, conching can take anything from a few to more than 70 hours. The temperature and frictional effect are generated by a type of agitator or mixer or by rolling in the longitudal conch. The most delicate couverture has to be monirated carefully; its often the worker at the machine who decides when a process is finished and when to intervene. Today, state-of-the-art, fully automatic conches are generally used. However, the best flavour is still achieved with longitudinal conches similar to those used in the nineteenth century. With dry conching, the flakes of chocolate mass are heated frictionally to between 60 and 90C. The dark brown, rather dry mass is turned and sirred. The rise in temperature causes the water to evaporate and this rising water vapour removes any volatile substances, such as acetic acid produced during fermentation. The mass has an initial water content of approx. 1.7 percent; this is reduced to just 0.6 to 0.7 percent.

During plasticising, the dry particles are covered in cocoa butter during constant stirring; the mass takes on a silky gloss. The senses now come into play with thr eyes making visual assessment of mixture. The aromas should unfold and merge; this is checked every three to six hours. The fine gloss starts to from. Once the desired gloss has been attained, liquid cocoa butter is added to liquefy the mixture. Before further processing, the warm couverture is then poured into heated tanks and stored for a maximum of two days.

The longitudinal conch In simple terms, conching transforms chocolate mass into a gorgeous product. The longitudinal conch is the most effective conching tool and, with its gentle action, it allows the most delicious flavours to develop. Felchlin still uses three longitudinal conches, each with four troughs and rollers, manufactured in the 1930s by U. Ammann in Langenthal. Thise conch looks rather like a paddle steamer and operates in much the same way: the wheel moves two horizontal connecting rods, one in front and one behind. The wheel rotates in the centre of the machine; the cast-iron troughs are located on either side. The lids used to cover the troughs are curved and painted a milk-chocolate brown. A steel roller is attached to the end of the connecting rod and this rolls the chocolate mass eveny backward and forward over a granite bed. The troughs are not heated; the intense heat that, depending on the duration of conching, is generated at the pedestal is the result of this motion, the constant friction and rolling action. Crashes and bangs can be heard as the mass smacks into the corners under the lid. However, the roller must never jump or knock. It is crucial that the right temperature is attained and this is no mean feat. There is no skill in simply pushing a button to start the heating process, however, there is an art to generating heat by applying just the right amount of friction. With longitudinal conches, it is possible to generate a temperature of 75C or more; 60-70C is the minimum. A certain temperature must be reached after 24 houres; if this does not happen, it cannot be corrected.

More on conching:

The conching machine is a special agitator for refining chocolate. Both physical and flavour-forming processes take place that are extremely important for glaze and aroma of the chocolate.

Slow conching: in the mechanical longitudinal conch, the chocolate mass is slowly rolled and aerated between granite stone and steel rollers for two to three says. The frictional heat has liquefying effect without any loss of the delicate aromas and fruit acids (see figures above).

Rapid conching: modern method that prepares liquid chocolate in just a few hours. Agitators with large shearing forces and rotational speeds can be used for rapid stirring, heating and the cooling of the mass.

Summer of 2011 visiting Fechlin and admire the longitudinal conching, thanks to Sepp and his wonderfull team.

Tempering The finished couverture to be moulded is cooled from 45-50C to 26-28C in a tempering unit and then re-heated to 29-32C. This produces uniform crystals in the couverture, which give the chocolate the desired texture and appearance.

Moulding, cooling and packaging The liquid, tempered chocolate is poured into the mould, cooled, knocked out of the mould and wrapped in compound foil or put into bags and then packed in cardboard boxes.

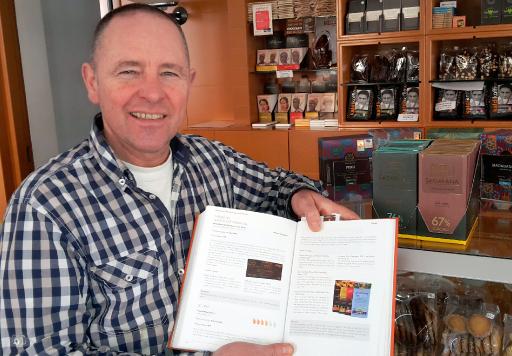

The presentation of the Grand Cru couvertures of Felchlin in my shop, sold in drops and bars with details to learn about and why this is such a fine chocolate!

next part: The Composition Every Detail Counts.

More on Felchlin and conching find out at chocolate friend Vera Hofman

Found this nice mail few weeks ago in my mailbox, like to share it.

The Art of Chocolate. From the Finest Cocoa to Exquisite Chocolate. part 6

By Vercruysse Geert, 2012-01-12

Published by Max Felchlin AG, Schwyz, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary. (2008)

Since visiting Felchlin 2010 and2011, I must admit Im addicted to there chocolate and there philosophy. This book is to interesting not to blog, so I must share this on my blog.

The Journey: From the Farmer to Basel.

After selection, the dried beans are generally transported as bulk goods in the hold of the ship (for example, cocoa from the Ivory Coast) or, more rarely, in sacks, and then taken on the long journey to their destanation for further processing, for example, to Switzerland. In the most cocoaproducing countries, the ships dock in special ports that are sometimes named after the cocoa that is loaded there. One example of this is Maracaibo, a port in Northwest Venezuela between the Lago de Maracaibo and the Caribbean Sea.

Beans from Beni in Bolivia have a particularly long journey. First of all, they are shipped about 1200 kilometres along the waterways in the Amazon Basin to the nearest town and, from there, along the first mountain pass through the Andes to La Paz, the capital of Bolivia, which is located at an altitude of 5200 metres above sea level. From La Paz, the journey continues across the Altiplano* and the second pass through theAndes, about 4300 metres above sea level, and then down to the Pacific Coast as far as Arica in Chile. After travelling a total distance of some 1600 kilometres by road, the beans are loaded onto ships and taken northwards along the coast via the Panama Canal and finally 12600 kilometres across the Atlantic to Rotterdam or Amsterdam, where the containers are transferred to a freighter and carried a further 850 kilometres up the Rhine to Basel. In Basel, the ship arrives in dock I. Here, the cargo is unloaded and the valuable sacks loaded onto pallets and stred in a warehouse until it is time for further processing.

*Altiplano: a plateau of the Andes, covering two thirds of Bolivia and extending into S Peru: contains Lake Titicaca. Height: 3000 m (10 000 ft.) to 3900 m (13 000 ft.)

Depending on weather conditions, the journey of the Beni beans takes two to three months and covers a total distance of more then 16000 kilometres; this is about 40 percent of the circumference of the globe. During this long journey, the fermented and dried cocoa beans are subjected to several changes of temperature and climate: from the warm, humid air of the Amazon Basin to the cold, dry air of the Altiplano and Andean passes; from the damp sea-air of the Pacific to the warm, humid air of the Panama Canal and, finally, a long cooling period crossing the Atlantic. The 6.5 percent moisture content of the beans after drying has to be maintained at all times. The beans always need sufficient air. They are transported in jute sacks or in sacks made from plasticised, air-permeable fabric. In containers, the beans can sweat, irrespective of whether theyre packed in sacks or as bulk goods: the containers are lined with corrugated card and paper to absorb any condensation. When carried along the Rhine, they are occasionally aerated by opening the sliding roof above the hold.

AMAZONAS RIO BENI IN BENI BOLIVIA

The Art of Chocolate. From the Finest Cocoa to Exquisite Chocolate. part 5

By Vercruysse Geert, 2011-12-19

Published by Max Felchlin AG, Schwyz, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary. (2008)

Since visiting Felchlin 2010 and2011, I must admit Im addicted to there chocolate and there philosophy. This book is to interesting not to blog, so I must share this on my blog.

The Bean From Harvesting to Shipping

The picked, ripe an healthy cocoa fruits are cut open. The beans are removed and transferred to wooden fermentation boxes that are not exposed to direct sunlight. This is the traditional and most authentic fermentation method; other modern methods, tailored to large-volume fermentation, are not as natural.

Fermentation Before fermentation, the beans are first inspevted and any rotten or mildewed beans discarded. Fermentation starts a maturation process, which involves microorganisms initiation the fermentation of sugar in the pulp, thus generation heat. The fermentation process kills the seedlings in the beans and relaeses an intense odour and juice runs out of the box. With wine, fermentation ends with cooling, however, with cocoa beans, it ends with drying. Experience gained over the centuries, as well as more recent experiments, have helped to determine the exact point when fermentation is over. Criollo, for example, has to ferment for between two or three days, Nacional for between four to five days and Forastero for between seven to eight days (depending on the hybrid). Experience is also necessary for controlled fermentation in boxes: the beans have to turned regularly to ensure sufficient aeration. Other factors that are key to successful fermentation are air humidity, temperature and the size of the boxes (area, height, width). The type and quality of the wood (soft, hard) also play a role.

Drying After fermentation, the cocoa beans have to be dried with the shrivelled, dry pulp. The best method is a natural one of simply drying the beans in the sun. The fermented beans are spread out in shallow wooden trays or on racks covered with mats made of natural fibres; in the event of sudden rainfall, the mats can simply be rolled up. Drying has to be monotored continuously (almost a daily occurrence in the Tropics), or if the sun is too strong, the beans have to be covered quickly. Three days in the blazing-hot sun is dangerous as the beans are dry on the outside but still moist on the inside; this means that will later sweat, give off moisture and then go mouldy during transportation or in storage. Depending on conditions and variety, drying takes between three to eight days. When shipped, beans should not contain more than 6.5 percent moisture.

FERMENTATION METHODS

Fermentation is a natural, spontaneous process that has a major influence on the quality of the flavour of cocoa. By using suitable infrastructures and methods, its possible to control the process and thus the resulting flavour.

Unfermented : the beans start to ferment spontaneously in the transport containers but with no control whatsoever. They are then taken straight to the drying stage, which means that virtually no fermentation takes place. Quality: poor.

Piles : the beans are collected into piles, covered with banana leaves and then left to ferment spontaneously. No infrastructure is required; the process is difficult to control. Quality: moderate to good.

Sacks or baskets : the beans are left to ferment in transport sacks or baskets. Simple infrastructure; only suitable for small quantities. Quality: moderate to good.

Boxes : the beans ferment in wooden boxes and are periodically turned, aerated and checked. Good control; relatively expensive infratructure. Quality: good to very good.

Selection Buyers differentiate between different qualities of cocoa beans. Thes differences are nothing to do with the actual variety, rather they are the result of the preceding stages, from cultivation to drying. The qualities selected have different names, depending on the country of origin.

For example, in the Dominican Republic, the highest quality is Hispaniola; the buyer has a say in processing and can, for instance, have any beans that are too large or too small removed to ensure uniform roasting sesults: beans that are too small quickly burn and those are too large are not roasted all the way through. In the Dominican Republic, the poorer quality bean is known as Sanchez. Local selection is important as this is the only way to determine the quality. Although the flavour can be influenced at a later stage (roasting, conching), the basic quality cannot (bean variety and size, fermentation, drying).

Most chocolate producers buy cocoa from traders in Europe, for example, in Geneva or Amsterdam. However, Felchlin does things differently. The specialists from Schwyz travel to the place of cultivation, taking the long journey and sometimes arduous communication in their stride in order to buy the cocoa beans at source. This enables them to use their expertise, to astablish relationships abd exert a direct influence on the properties of the beans. This personal commitment has a positive effect on qulity and any variations are relatively easy to prevent.

DRYING METHODS

The fermented beans still contain approx. 60 percent water. This has to be reduced to less than seven percent so that the beans can be tranported and stored. Slow, careful drying is important for the resulting quality and can take up to seven days.

Sun-drying The beans are spread out to bamboo mats or wooden tables and, depending on weather conditions, protected from strong heat or heavy rains. Its easy to turn and move the beans and the condition of the beans and the drying process can closely monitored. However, a large amount of manpower is needed and the long drying time is weather-dependent. Quality: good to very good.

Artificial heat The beans are heated in long, deep trays by bloxwing air that has been heated artificially through a perforated base. There are also other systems for transferring heat. Large quantities can be dried quickly, even in poor weather conditions. However, drying is uneven, often forced and, in the worst-case scenario, the beans can be contaminated with smoke from the combustion facilities. Quality poor to satisfactory.

Next time: The Journey From the Farmer to Basel